When it comes to his work as a guitarist, composer and, most recently, as a devotee of Tibetan overtone singing, New Yorker Baird Hersey virtually epitomizes the often overused honorific “unsung hero.” But such a characterization, at least in Hersey’s case, is misleading. For while he’s never achieved widespread popular acclaim-even in the more rarefied terrain of “experimental” music-he is deeply respected among his peers, among discerning critics, and among knowledgeable aficionados of progressive music as an innovative, if idiosyncratic, artist. He’s received commissions from Harvard University and the New Mexico Council for the Arts; he’s been a featured performer at the Berlin Jazz Festival; he’s opened for Philip Glass and the Grateful Dead; he’s had the rare honor of having an entire Hearts of Space radio broadcast devoted solely to his music; and he’s even been on MTV. From blues-influenced psychedelic rock to jazz fusion to musique concrete, proto-electronica, reggae, new wave and new age, Hersey has seemingly absorbed and then jettisoned a dizzying number of musical styles and genres throughout his long, eventful career as a guitarist/synthesist/vocalist/composer. In the process, he’s assembled a formidable body of work as a musician and aural explorer.

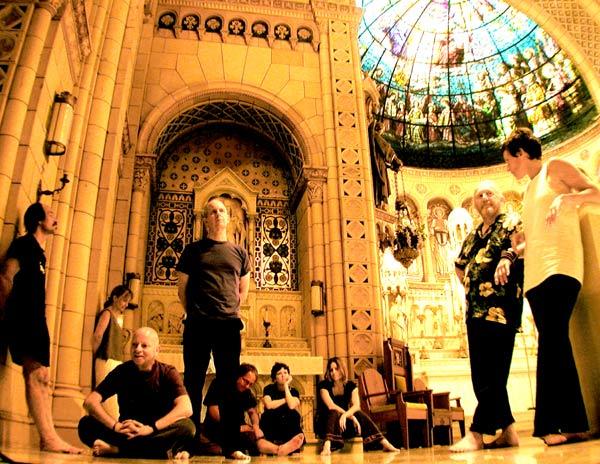

But it was his discovery of Tibetan overtone singing and later Ashtanga yoga that profoundly altered both his music and his life. Like John McLaughlin before him, Hersey’s spiritual path has taken him from the prestigious ranks of the guitar virtuoso to the esoteric circles of Buddhist philosophy and yogic practice. But Hersey’s musical quest for the Great Om at the center of the universe really began in the late 60’s with Swampgas, whose Grateful Dead-derived psychedelic blues rock was symptomatic of the times. As with many similar groups Swampgas was a victim of that turbulent age, surviving just long enough to record and release one album in the wake of the acid fallout of psychedelia. In 1975, Hersey founded the engagingly eccentric jazz-funk group Year of the Ear. The group released three albums of tightly-knit, high energy ensemble fusion that merged Miles, Mingus, and Mahavishnu into a fascinating bitches brew of big band funk and avant-jazz. In the late 70’s, Hersey’s interests veered more and more toward minimalism and sonic experimentation. Coessential, his 1977 collaboration with the brilliant anarchic percussionist David Moss, is a little-known though highly treasured gem of avant-garde soundscaping. Equally impressive is his even more obscure solo album from 1980 ÔDO OP8 FX, a minimalist tour-de-force of early electronica featuring Hersey’s soaring guitar atop bubbling analog synthesizers and driving sequencers. Throughout the 80’s Hersey dabbled in new wave and synth-pop with the groups FX and Artificial Intelligence, though most of his time was devoted to producing music for television and other media in the Big Apple. Always an admirer of Tibetan music and at one time a member of David Hykes’ Harmonic Choir, Hersey reinvented himself in the 90’s as a disciple of overtone singing, and in the process formed his own harmonic collective called Prana. In many ways, Prana represents Hersey’s boldest musical venture yet-a kind of spiritual-musical quest for the most fundamental vibrations that hold together the harmony of the spheres. Though Hersey has now seemingly unstrapped his guitar forever, its ghostly echoes still resonate in the massed voices of Prana’s cosmic chorus, a fitting reminder that there is after all only one song with its endlessly rich and varied melodies. It really has been a long, strange trip for Baird Hersey.

AI: You’re probably best known as a guitarist and composer. Are you self-taught or do you have formal training?

BH: For the most part as a guitarist, I’m self-taught. I played along with records. I was very fortunate in high school to have a wonderful music teacher who saw something in me and encouraged me to compose. In college, I studied composing, orchestration, arranging, and improvisation.

AI: Over the years, you’ve produced an eclectic catalog of highly exploratory music. What were some of your most important early musical experiences and influences?

BH: When I was about 5, my mom took me to a Memorial Day parade. The sounds of the brass bands sent chills up my spine. I grew up in a house where music was always playing, everything from Miles Davis to Rachmaninoff, Ella Fitzgerald and Bach. My mother was also a theatrical producer, so there were also a lot of Broadway musicals playing, as well. I was at the first performance The Beatles did in the U.S. It was a rehearsal the afternoon of their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. That, needless to say, had a big impact on me. As I got into my early teens, the birth of FM radio took music on the airwaves in a more adventurous direction. WNEW was on in my room night and day. I became a big fan of Eric Clapton through his work with John Mayall and later with Cream. I grew up in New York City, so between the Cafe A-Go-Go and the Fillmore East, I heard Muddy Waters, Paul Butterfield, Traffic, Blood, Sweat and Tears, The Grateful Dead, The Staple Singers, Jethro Tull, Ritchie Havens, Chicago, Procol Harum, and countless others. In 1967, I had the good fortune to be part of the film crew that shot The Monterey Pop Festival. The festival drew on the burgeoning music scene in California with acts like Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, Moby Grape, The Who, and most importantly Jimi Hendrix who at that moment changed guitar playing forever-especially mine!

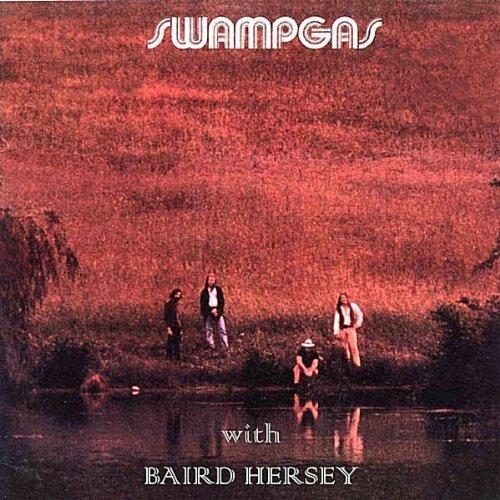

AI: You released one album in the early 70’s on the Buddah label with the group

Swampgas. Can you provide some background about the group’s origins and your association with the band?

BH: We had all been playing in clubs on Long Island and the group really came together when we went to Nova Scotia where we rehearsed in a shack on the ocean using a generator to power our equipment. One of the producers of Woodstock, Artie Kornfeld, signed us to Buddah after his wife saw us open for the Grateful Dead in Connecticut in the spring of 1970. We recorded the album the following summer. Because of business problems the finished album sat on the shelf for a year and a half. As a result, the band fell apart. When the album finally came out, I only heard about it because there was a review in Billboard.

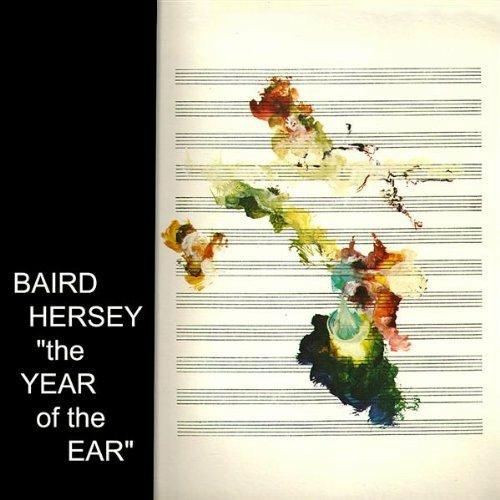

AI: After Swampgas you led the jazz fusion group Year of the Ear. How did this group come about?

BH: After Swampgas broke up, I went back to school to study music. I studied with the trumpet player/composer Bill Dixon. When I got out of school, fusion was just starting to happen. It wasn’t what we think of today. It was vital and alive with bands like Weather Report, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and Return to Forever. And of course in the driver’s seat, there was Miles Davis, who I saw many times, most notably three nights in a row at the Cafe A-Go-Go with the Live Evil band. That totally blew my mind. Year of the Ear was together 5 years and did three albums.

AI: In the late 70’s you seemed to opt for a more minimalist approach to music, a decision that resulted in a memorable collaboration with percussionist David Moss as well as an innovative solo album of early electronica beguilingly titled ÔDO OP8 FX. What motivated this change in musical orientation?

BH: I was feeling the weight of leading a 14-piece band for 5 years. After we played the Berlin Jazz Festival (http://www.youtube.com/user/TheYearoftheEar/videos) I decided to give it a rest. Synthesizers were just beginning to be available, and I found I could do a lot on my own.

AI: Coessential, your collaboration with Moss, has some strikingly original guitar work – almost as if you were creating sound sculpture with an instrument that, particularly in 1977, wasn’t ordinarily associated with avant-garde sound construction. Was this your intent at the time?

BH: David and I worked together in collaboration. Most of what we played on the album came out of the improvisational vocabulary of sounds that we evolved together. I composed four of the pieces and David did a solo piece. The rest were structured improvisations.

AI: Your 1980 solo album ÔDO OP8 FX is regarded by many serious “underground” music aficionados as a pioneering work that anticipated much of the electronica of the 90’s. How did this project come about?

BH: That album was recorded direct to 2-track, no overdubs. In fact, on one tune “The

Minotaur” I play feedback guitar melodies with my left hand and synth with my right hand. It was definitely influenced by the minimalist composers. A funny thing happened while I was recording one track. It had a repeating minimalist synth figure. The engineer disappeared for a few minutes during playback of a take and the studio doorbell rang. I didn’t know how to buzz the person in, so I ran up the stairs and opened the front door. Who’s standing there? Phil Glass! In the background droning along was do-be-do-be-dobe. I thought to myself “BUSTED!” Hahaha! That record was before there was such a thing as new age or trance music.

AI: Probably like most people who bought the original vinyl edition of ÔDO OP8 FX, I was intrigued by the mysterious title. Can you shed some light on what the title refers to?

BH: The title is a phonic device. If you notice, the first “O” has a little hat over it, which makes it an “aww” sound. So the letters phonetically say “Audio Opiate Effects,” meaning the sound put you in an altered state. With “opiate” in the title my dad was a little worried that I was on drugs, which I wasn’t. I assured him it was only the sound that altered your brain chemistry.

AI: After ÔDO OP8 FX, your work took yet another dramatic turn, even flirting with new wave, reggae and electro-pop with the groups FX and Artificial Intelligence. FX, in particular, had a fair amount of success. Can you provide a synopsis of your work with these groups?

BH: I had always played with what are now called “jam” bands on the side. I felt a pull to go back to rock. So I put FX together. We recorded an album and won the “Best Unsigned Band” contest on WNEW. We even had a video on MTV (http://www.youtube.com/user/FXStimulation/videos). We played around, but somehow it never really got off the ground. Then I got married, had three kids, and started writing music for television. When the pull came to play out, I had all this gear I’d been using for the T.V. work and a studio in my house. So I did the Data Drone album (http://www.youtube.com/user/DataDrone/videos). Artificial Intelligence was kind of a hobby band.

AI: You seemed to have undergone a life-changing experience when you started practicing yoga in the late 80’s. What precipitated this change in lifestyle?

BH: In 1988, I started doing yoga. In 1997, I was introduced to Ashtanga yoga, which is still my daily practice. It’s a very intense, physically demanding practice. Something opened in my body and my mind and absolutely turned my life upside down but also led me to the music I now do.

AI: Did this spiritual awakening lead directly to your interest in Tibetan ritual music and eventually to the formation of your current musical project Prana?

BH: I don’t know how awake I actually am, but I am pretty happy, which is not how I was when I was younger. Actually, I’ve been interested in Tibetan music since the early 70’s. On the first album Year of the Ear did for Arista, there’s a piece called “Tibet,” which is what an avant-garde big band sounds like when it’s trying to play Tibetan temple music.

AI: Can you briefly explain the goals-both musical and spiritual-you’re trying to achieve in Prana?

BH: Musically, we’re just trying to create something beautiful. My composing style is slow, minimalist. But everything I have done musically in my life shows up in there somewhere. I really feel like all my other work has led me to this point. From a spiritual point of view, we’re just trying to provide people with a moment of peaceful contemplation.

AI: You’ve spent a fair amount of time in India. How have your experiences there influenced your attitudes both toward your approach to music and to your life in general?

BH: I went to India to study with a yoga master, Sri K. Pattabhi Jois, who was the main teacher of Ashtanga yoga. He died in 2009. Prana’s music is a mixture of Western vocal music and the musics of Tibet, Mongolia, and India.

AI: As an adherent of harmonic singing, were you-like many people in the U.S.-first introduced to it through David Hykes and his recordings with the Harmonic Choir?

BH: Yes and no. I was introduced to overtone singing by listening to Tibetan monks and

Tuvan throat singers. I taught myself. I later met David and worked with his group for about a year. I learned a lot from him in terms of refinement of my technique. He is a master and pioneer in the field.

AI: Prana, of course, doesn’t include your guitar in its repertoire. Do you still play and compose for the instrument?

BH: There are only two times in the last 15 years that I’ve picked it up. The first time was with David Hykes’ group and the other was to do some gigs with Krishna Das. I never say never. I may get back to it someday.

AI: Do you ever see yourself returning to your roots in jazz and rock at some point in the future?

BH: Probably not. It would be more on the World music side of things: lots of percussion.

AI: What are your immediate musical plans and objectives for the near future?

BH: Prana is just finishing a record and will be playing some festivals this summer. I recorded a requiem for September 11th last summer with a 24-voice choir. It needs to be edited, mixed and mastered. I wrote a book on sound meditation that I’m hopeful will come out early next year. I also have a video cook book on youtube called “The Invisible Vegan” to which I add about a dish a month. I’ve been a vegan since 1973.

BAIRD HERSEY DISCOGRAPHY

GROUPS & COLLABORATIONS

w/ Swampgas:

Swampgas (1972, Buddah Records LP)

w/ Year of the Ear:

Year of the Ear (1975, Bent Records LP)

Lookin’ for That Groove (1977, Arista Records LP)

Have You Heard (1978, Arista Records LP)

w/ David Moss:

Coessential (1977, Bent Records LP)

w/ FX:

FX (1981, Bent Records LP)

w/ Artificial Intelligence:

Data Drone (1990, Bent Records CD)

w/ Prana:

Waking the Cobra (1999, Hersey Music CD)

The Eternal Embrace (2004, Hersey Music CD)

Gathering in the Light (2007, Satsung CD)

SOLO

ÔDO OP8 FX (1980, Bent Records LP)

All of the above albums are available from iTunes

Visit http://www.pranasound.com for information about Baird Hersey and Prana.

By Charles Van de Kree

Fruits de Mer Records specialize in vinyl only releases featuring contemporary bands covering songs – many quite obscure -from the 1960s and early 1970s. The Lucid Dream are from Carlisle, Cumbria, UK and have been together since 2008. Their new single on Fruits de Mer’s Regal Crabomophone label includes a Lucid Dream original and a cover song.

Fruits de Mer Records specialize in vinyl only releases featuring contemporary bands covering songs – many quite obscure -from the 1960s and early 1970s. The Lucid Dream are from Carlisle, Cumbria, UK and have been together since 2008. Their new single on Fruits de Mer’s Regal Crabomophone label includes a Lucid Dream original and a cover song.

Fruits de Mer Records specialize in vinyl only releases featuring contemporary bands covering songs – many quite obscure -from the 1960s and early 1970s. nick nicely is one of those pop-psych craftsman who has yet to get his due, despite brushes with major labels and producers. Hilly Fields (1892) was released as a single in 1982 and is one of those instantly infectious songs that immediately brings to mind The Beatles circa Magical Mystery Tour or XTC at their very best. It’s also embellished with cool hip-hoppy scratching, though the music couldn’t be further from hip-hop. And if you’ve ever wondered about the title, the promo sheet notes that Hilly Fields is near where Nick lived with great views of both London and Kent.

Fruits de Mer Records specialize in vinyl only releases featuring contemporary bands covering songs – many quite obscure -from the 1960s and early 1970s. nick nicely is one of those pop-psych craftsman who has yet to get his due, despite brushes with major labels and producers. Hilly Fields (1892) was released as a single in 1982 and is one of those instantly infectious songs that immediately brings to mind The Beatles circa Magical Mystery Tour or XTC at their very best. It’s also embellished with cool hip-hoppy scratching, though the music couldn’t be further from hip-hop. And if you’ve ever wondered about the title, the promo sheet notes that Hilly Fields is near where Nick lived with great views of both London and Kent. Fruits de Mer Records specialize in vinyl only releases featuring contemporary bands covering songs – many quite obscure -from the 1960s and early 1970s. A few months ago Fruits de Mer released the excellent Sorrow’s Children: The Songs Of S.F. Sorrow, a re-recording of The Pretty Things 1968 classic S.F. Sorrow, with each track contributed by a different contemporary band. And now the label keep The Pretty Things in the spotlight with this new single.

Fruits de Mer Records specialize in vinyl only releases featuring contemporary bands covering songs – many quite obscure -from the 1960s and early 1970s. A few months ago Fruits de Mer released the excellent Sorrow’s Children: The Songs Of S.F. Sorrow, a re-recording of The Pretty Things 1968 classic S.F. Sorrow, with each track contributed by a different contemporary band. And now the label keep The Pretty Things in the spotlight with this new single. I first became aware of Ararat when I received the first CD they recorded, Musica De La Resistencia as a promo freebee in a package of other CD’s I’d ordered. Figuring it to be a throwaway, I admit it took me awhile to listen to it, but when I did, wow, I was knocked out. I’m quite pleased to say that it’s follow up is knocking me out too!

I first became aware of Ararat when I received the first CD they recorded, Musica De La Resistencia as a promo freebee in a package of other CD’s I’d ordered. Figuring it to be a throwaway, I admit it took me awhile to listen to it, but when I did, wow, I was knocked out. I’m quite pleased to say that it’s follow up is knocking me out too! Motion Sickness of Time Travel is the moniker for solo electronic artist Rachel Evans (she’s also a member of Quiet Evenings). Since 2008, Rachel has been an extremely busy woman, with over 20 releases under the MSOTT name (some LP’s, some EP’s), but this appears to be her most ambitious effort to date. This self-titled effort consists of just 4 tracks, ranging in length from 20-minutes to almost 25 minutes.

Motion Sickness of Time Travel is the moniker for solo electronic artist Rachel Evans (she’s also a member of Quiet Evenings). Since 2008, Rachel has been an extremely busy woman, with over 20 releases under the MSOTT name (some LP’s, some EP’s), but this appears to be her most ambitious effort to date. This self-titled effort consists of just 4 tracks, ranging in length from 20-minutes to almost 25 minutes. Nacosta return in the wake of last year’s superb 6-song EP Wilderness City with their latest, a 3-song EP called Liquor Eyes. Although they call themselves a psychedelic folk band, they quite easily cross over into the rock realm. In fact, nothing on this release could really be construed as folk music. It opens with the superb acid drenched rocker Secret Destroyer. Here again, as on their last EP, the band proves themselves masters of writing hook laden songs. But they allow their music to stray far enough into wild sonic territories to keep the psych heads interested too. The other two songs are perhaps not quite as hooky as that opener, but they still show the band in fine form. The semi-acoustic, frantically rhythmic title track showcases their lovely harmonies and the rumbling Coldwater Canyon swirls with colorful guitar licks as it builds towards quite a tasty psych freakout conclusion. The bonus here is that the band have designated this a free download, so head off to their website and grab yourself a copy!

Nacosta return in the wake of last year’s superb 6-song EP Wilderness City with their latest, a 3-song EP called Liquor Eyes. Although they call themselves a psychedelic folk band, they quite easily cross over into the rock realm. In fact, nothing on this release could really be construed as folk music. It opens with the superb acid drenched rocker Secret Destroyer. Here again, as on their last EP, the band proves themselves masters of writing hook laden songs. But they allow their music to stray far enough into wild sonic territories to keep the psych heads interested too. The other two songs are perhaps not quite as hooky as that opener, but they still show the band in fine form. The semi-acoustic, frantically rhythmic title track showcases their lovely harmonies and the rumbling Coldwater Canyon swirls with colorful guitar licks as it builds towards quite a tasty psych freakout conclusion. The bonus here is that the band have designated this a free download, so head off to their website and grab yourself a copy! Census of Hallucinations (CoH) were on a creative roll for years, cranking out outstanding albums at a steady pace. In recent years Tim Jones and the Stone Premonitions collective have released albums by a variety of projects, like Stone Premonitions 2010, Stella Polaris, and The Global Broad Band. And now, five years after their last album, Tim has resurrected CoH with himself on guitar, vocals and scribe of all lyrics, the Reverend Rabbit on bass, long time cohort Paddi on drums, and David “Ohead” Hendry on keyboards.

Census of Hallucinations (CoH) were on a creative roll for years, cranking out outstanding albums at a steady pace. In recent years Tim Jones and the Stone Premonitions collective have released albums by a variety of projects, like Stone Premonitions 2010, Stella Polaris, and The Global Broad Band. And now, five years after their last album, Tim has resurrected CoH with himself on guitar, vocals and scribe of all lyrics, the Reverend Rabbit on bass, long time cohort Paddi on drums, and David “Ohead” Hendry on keyboards.

Ginger is a four piece band from Zurich, Switzerland. What initially got me interested in Ginger was viewing their fan videos of their live performances on YouTube. Ginger fuses rather funky rhythms with (what many would consider) wailing guitar riffs. Tracks that are well worth mentioning include the almost Jimi Hendrix-like guitar driven The Wheel, the slower-paced eight-minute Painful Hours with guest cellist Stephanie Kobza, the country-rock 200 Horses with nice arrangements plus some well-played Hammond organ, the stylish Wild Bill and the truly poetic – another eight-minute song – Inside I’m Free which in reality I thought was nearly worth the price of admission alone. After I listened to this disc a third time, I also found to my liking Yeager, which possesses some fine wah-wah guitar effects with its lyrics paying tribute to famed Air Force general Chuck Yeager – who broke the sound barrier in 1947 while piloting an experimental Bell-X 1; and the bluesy Father that employs some enjoyable trumpet playing. It’s a little tough to accurately describe Ginger’s music because these four talented musicians play several genres – blues rock, some psychedelia and a certain amount of folk. It’s apparent that some of what Ginger has to offer their listeners consists of strong (both dual and lead) vocals, well thought-out writing (and playing) as well as in-depth, woven walls of sound within.

Ginger is a four piece band from Zurich, Switzerland. What initially got me interested in Ginger was viewing their fan videos of their live performances on YouTube. Ginger fuses rather funky rhythms with (what many would consider) wailing guitar riffs. Tracks that are well worth mentioning include the almost Jimi Hendrix-like guitar driven The Wheel, the slower-paced eight-minute Painful Hours with guest cellist Stephanie Kobza, the country-rock 200 Horses with nice arrangements plus some well-played Hammond organ, the stylish Wild Bill and the truly poetic – another eight-minute song – Inside I’m Free which in reality I thought was nearly worth the price of admission alone. After I listened to this disc a third time, I also found to my liking Yeager, which possesses some fine wah-wah guitar effects with its lyrics paying tribute to famed Air Force general Chuck Yeager – who broke the sound barrier in 1947 while piloting an experimental Bell-X 1; and the bluesy Father that employs some enjoyable trumpet playing. It’s a little tough to accurately describe Ginger’s music because these four talented musicians play several genres – blues rock, some psychedelia and a certain amount of folk. It’s apparent that some of what Ginger has to offer their listeners consists of strong (both dual and lead) vocals, well thought-out writing (and playing) as well as in-depth, woven walls of sound within. As a big live album fan that I’ve always been, I believe that I may like Ginger’s Seahorse CD a bit more than this From the Road disc. Don’t get me wrong, this nine song CD is still a fine effort and all but it simply didn’t grow on me as much as Seahorse had managed to. From The Road is a live document of what Ginger had performed while out on tour during the fall of 2010 with gigs happening in their hometown of Zurich, Switzerland and Binningen as well as a couple of German shows – those being in Berlin and Gottingen. Here, you get Ginger playing two classic rock covers plus tunes from the previously mentioned Seahorse CD and their first record LP Arlanda which I haven’t heard yet. Starts out with a ten-minute cover of Pink Floyd’s Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, the well-penned eleven-minute Crosstown Bar Blues, Jam, Winds Of Dust, Part II, Sugar Mama and the finale, an eight-minute tribute to Them’s Van Morrison with Gloria. CD’s sound quality is quite good – for it possesses that [like you are there] vibe and sound with a definite Jimi Hendrix influence obviously present. Front insert is an eight-page CD booklet with full color photos of Ginger’s live shows taken on this mini-trek. The bio sheet for this CD release notes: ‘From The Road’ reads like a menu – a seven course candle light dinner. For starter, the band chose a psychedelic interpretation of a piece by Pink Floyd, followed by steady rock, impulsive shuffle, a rhythmic delicate drum solo, some heavy blues, entangled double guitar parts and to top that off – a break out of some free improvisation. Couldn’t have said it better myself.

As a big live album fan that I’ve always been, I believe that I may like Ginger’s Seahorse CD a bit more than this From the Road disc. Don’t get me wrong, this nine song CD is still a fine effort and all but it simply didn’t grow on me as much as Seahorse had managed to. From The Road is a live document of what Ginger had performed while out on tour during the fall of 2010 with gigs happening in their hometown of Zurich, Switzerland and Binningen as well as a couple of German shows – those being in Berlin and Gottingen. Here, you get Ginger playing two classic rock covers plus tunes from the previously mentioned Seahorse CD and their first record LP Arlanda which I haven’t heard yet. Starts out with a ten-minute cover of Pink Floyd’s Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, the well-penned eleven-minute Crosstown Bar Blues, Jam, Winds Of Dust, Part II, Sugar Mama and the finale, an eight-minute tribute to Them’s Van Morrison with Gloria. CD’s sound quality is quite good – for it possesses that [like you are there] vibe and sound with a definite Jimi Hendrix influence obviously present. Front insert is an eight-page CD booklet with full color photos of Ginger’s live shows taken on this mini-trek. The bio sheet for this CD release notes: ‘From The Road’ reads like a menu – a seven course candle light dinner. For starter, the band chose a psychedelic interpretation of a piece by Pink Floyd, followed by steady rock, impulsive shuffle, a rhythmic delicate drum solo, some heavy blues, entangled double guitar parts and to top that off – a break out of some free improvisation. Couldn’t have said it better myself.