I’ve been acquainted with Paul Foley since the early Aural Innovations days, through his Melbourne, Australia based band Brainstorm. Brainstorm are tough to pigeonhole, occupying a varied musicial world that incorporates Space Rock, Progressive, Hard Rock and other influences. In the days of Aural Innovations as a printed zine we featured a review of the Brainstorm album Tales Of The Future, which included an interview with Paul that I recommend for good background information on the band and where they were at as of 1999 (link at the end of this article). Tales Of The Future was followed by Desert World in 2005. After that I would periodically receive mp3s from Paul of songs he was working on that I would share with the world on Aural Innovations Space Rock Radio.

Fast forward to earlier this year and a package arrives from Australia with two more Brainstorm CDs, and a BOOK. Paul is an amateur astronomer who had a column in his local newspaper the Central Victorian Weekly, and its successor the Bendigo Miner. Last year Paul’s essays from the column were collected in a book titled Beyond Earth, which I highly recommend. Paul has a flair for making science accessible and understandable. Functioning as professor, futurist, and musing philosopher, this collection was a pleasure to read, providing much food for thought, and inspiring more than a few questions.

What follows is a review of the two most recent Brainstorm CDs, and then an interview with Paul, first about Brainstorm and then the book.

Brainstorm – “Planetfall” (self-released 2012, CD)

Brainstorm – “Planetfall” (self-released 2012, CD)

Though released under the Brainstorm name, Planetfall is actually a Paul Foley solo album. Paul addresses what he considers the albums shortcomings in the interview, particularly the Midi rhythm section. But while the listener will detect this in comparison to other Brainstorm albums, Planetfall has beautiful guitar work and melodies, lots of well crafted Progressive Rock themes, and provocative lyrics that more than compensate for the limitations of Paul’s instrumental arsenal. Lyrically, the songs are less science/technology/sci-fi/futurist oriented than usual and more focused on the ills of the world, particularly war and socio-economic inequities.

Fortress First World opens the set and includes varied multiple guitar parts – acoustic, electric and nicely efx’d solos – that characterize much of the album. Ballad Of Mary McKillop demonstrates that the Midi can work well, adding a bubbling spacey vibe, and I like the section that combines melodic acoustic guitar with dark sci-fi soundtrack electronics, plus Paul’s lulling flute, which all come together nicely on this song that goes straight for the Catholic clerical throat. The instrumental Green Zone has a Prog infused B-movie sci-fi soundtrack and old time video game feel, and later a tasty guitar solo. Another simple yet beautifully executed guitar solo can be heard on Thirty Grand A Second. Cyren Call is a 16 minute Space-Prog epic with an early 70s feel. There’s a lot happening here. It’s got ELP keys with a spacey, darkly Gothic edge, plus flute that at times brings to mind Jethro Tull, and at others early Genesis, and well placed guitar licks. But we’ve also got that sci-fi soundtrack feel, and Paul is deep in Progressive Rock development as we segue through an ever evolving range of themes. Just Another Morning and Planetfall are both musically uplifting, yet lyrically somber folk(ish) songs. Intelligent Design combines spacey Prog with a traditional… perhaps Celtic pub rock feel, and includes some intensely acidic instrumental interludes. I like the combination of bouncy rhythms and keys that are both ethereal and sci-fi searing on Nothing To Fear. Breakin’ Out is part Bluesy feel good groove tune that you just might be able to dance to, yet also includes spacey symphonic keys, as well as the album’s trademark cautionary lyrics. Finally, Forest Reason has a spaced out intro, with its dark rumbling drone and ethereal flute melody. When the song begins it has a dreamy Celtic sound and luscious flute and acoustic guitar passages. Be sure and read the interview for Paul’s commentary on the album and more (hopefully) upcoming solo works.

Brainstorm – “The Spiral Stair” (self-released 2013, CD)

Brainstorm – “The Spiral Stair” (self-released 2013, CD)

The Spiral Stair is the latest from Brainstorm and returns to the full band format. The musicians worked on this album for years and the result is ten songs and lots of variety.

Breakout is a rock and roll song, given a Space Rock edge with electronics and space-wave synths. I mentioned Celtic influences a couple times in my Planetfall review, and there’s something about this song that reminds me of the Irish band Horslips, though only during the verse. There’s a spacey synth and piano led transitional bit later, adding a slow and nicely melodic guitar solo that all together makes for an intriguing Space-Prog contrast, yet it all flows seamlessly. The lazy pace and grungy guitar give My Bird In The Sky a Neil Young Down By The River vibe, though the spacey keys and completely non-Neil vocals guide the music into dreamy melodic Space-Prog land. Scorpio Landscape is a pleasantly flowing and grooving instrumental that has a Pop music feel, but includes flute and light electronics, and shifts gears enough to be elusively complex. It’s accessible yet adventurous in the way that, say, later period Camel was. Trouble In Paradise is another accessible rocker that takes interesting thematic twists and turns. Crocodilian Motion is brimming with a rhythmically off-kilter sense of Funk and Soul, though it later transitions to soulful flowing Pop-Prog, with a great combination of flute and organ. Walls may not sound like the Doors, but the main theme sure sounds like the late Ray Manzarek sitting in on organ. Das Elektronisches is different from anything I’ve heard Brainstorm do. It starts off as a dreamy, meditative Space-Classical piece, and then abruptly shifts to a Neu!/Kraftwerk brand of electronica with healthy doses of Prog keys and gliss guitar. This one really took me by surprise. Tranquil Fantasy includes some of the album’s most gorgeous melodies and chunkiest guitars. It has a Hawkwind feel at times, but veers 180 degrees to flowing piano led segments. And speaking of chunky guitars, Surrender has an easy paced vibe but rocks hard, with guitar and vocals that recall 70s hard rock, plus periodic organ and space synths. Wires wraps up the set in true Brainstorm fashion, running the gamut from Squeeze-like Pop, to heavy guitar rock, to acoustic Folk, Psychedelia and soulful rock, and bouncing harmoniously from one to the next and back again.

These descriptions may sound all over the map but Brainstorm make it work. The band excel at bringing together a contrasting variety of elements and making them fit like gloves.

I conducted the following interview with Paul Foley via email.

Brainstorm

Aural Innovations (AI): Your 2012 Planetfall CD was the first since 2005’s Desert World. It lists the members and I recognize some of the old names. I don’t see any lineup listed on your latest CD, The Spiral Stair. Who was in the band for that album?

Paul Foley (PF): A very good question. An even better question is why the names aren’t on the cover in the first place. Exhaustive research last weekend led me to the clever strategic move of asking Jeff, who did the cover art, about it. Expecting a breathtaking intellectual chain of inspired reasoning, harking back to such paradigms as Led Zeppelin 4 and Spinal Tap’s Smell the Glove, to explain this daring departure of ours from traditional album packaging, Jeff thought for a minute, had a close look at the album cover to refresh his memory, then came up with the brilliantly original reply: “Oops.” We had all looked the cover over carefully (so we thought) before giving it the thumbs up, and none of us spotted that the names weren’t on it. The moral of this story, which we should all know well enough by now, is that no-one should ever do their own proof-reading. For the record (sic) the lineup is the same as for Desert World and Tales of the Future: Steve Bechervaise, Jeff Powerlett, Vittorio Di Iorio, Paul Foley and Craig Carter. In fact, we’ve had the same people now for over 20 years.

AI: In recent years you have periodically sent me individual songs that I’ve played on AI Space Rock Radio, and I got the impression that they might have been solo works? Am I off base and those were early version of songs that ended up on The Spiral Stair?

PF: Sure enough, they were solo projects, recorded by me at home. The problem is that, due to logistical constraints, day jobs, families, not living in the same city as one another and so on, the band takes a hell of a long time to put songs together. We only get together fortnightly for rehearsals, recording and writing. The music sounds much better when we do it that way, of course, but it all takes soooooooo loooooong.

Anyway, back in 2010 I had a kind of anti-epiphany, realising that I had a backlog of material, in my head, on paper and in the form of rough demo recordings, which at our current rate of songwriting and recording would have seen us still working on them – without allowing for any new stuff – when I was 148 years old. At the time, i.e., in 2010, we’d already been doing Spiral Stair for five years, and it was still another three years before even that album finally came out.

There were, and still are, a lot of songs, not just mine but whole-band ones and solo projects by others, some written as far back as 2005, lying around, which didn’t make it onto Spiral Stair. Vittorio has an entire album’s-worth of music he’s written and recorded, which needs only a little polishing to be worth releasing in toto.

It was a sad situation. I wanted to get the songs out, and began recording them properly at home, not just as demos, but with as much polish and professionalism as I could achieve.

This wasn’t a problem to the others in the band. They understood the situation, and were happy for me to put the songs out under the name Brainstorm. We’re good friends and have been together far too long to worry about pride and other pointless preoccupations. Music is supposed to be fun, a special way of expressing thoughts and feelings. As soon as personal politics becomes a factor, you’ve lost the point of what you’re doing, it’s not fun any more, and you might as well stop altogether. That was the album that became Planetfall.

There were compromises on quality, to be sure. My shortcomings musically, as well as in an engineering and production sense, were clear and obvious on all the tracks, but it seemed to me that it was a better call to do this, than the option of burying most the songs, and their never making it onto an album at all.

The album’s failings are mainly in the standard of production and the instrumentation and playing of the rhythm section in particular, which was done via midi on computer, and sounds glaringly fake. The album’s strengths are the chance I had of creating multiple layers of instrumentation and, just possibly, in the lyrics, which have moved on from the band’s earlier Sci Fi theme into politics and philosophy. The only explanation I can offer for this is that I seem to have got grumpier in my old age.

Some of these (Planetfall) songs are now on Youtube with accompanying videos: Fortress First World, about the polarisation of the world into rich and poor, Ballad of Mary McKillop, about Catholic paedophilia, Green Zone, about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Intelligent Design, about religious creationists (idiots).

Even after Planetfall, I still have another album’s worth of solo songs left over. The band album, Spiral Stair, which came out in November 2013, is what we’re working to promote now, but I hope that this second solo album can be released later this year. One of its songs, Taliban, featuring the original singing bearded Taliban Dalek, is up on our Youtube channel (CLICK HERE to check it out).

The band’s songwriting and recording bottleneck moved us to try an interesting solution. We’ve set up of a “virtual C-drive” on the internet. It’s a hidden site, which only band members can get into. Rather than try to use valuable group meeting time to work on material, we’re now able to record a lot of our ideas, whole tracks, overdubs, etc, at home, then post them onto this website, where the others can listen to them, download them to their computer and work on their own sections within the track.

Say Craig does a rhythm track, he can put it on the website. Then, at their own leisure, someone else can save it, add an overdub, then post it back. This can all be done at times of individual convenience, after work during the week or whenever, rather than having to wait for those precious few hours when we’re all free at the same time and physically together in the one place. It works very well, and has enabled us to remember and build on ideas, to move ahead on several tracks simultaneously in parallel, rather than having to do things in strict sequential order, and has freed up a lot of time and creativity.

AI: I saw on your web site pics from the band’s 25th anniversary this past November. How many of the original, or at least early members from the 90s participated?

PF: We’ve had the same lineup for around 20 years now, since Vit the “new” drummer joined. Not only is he the new guy, he’s also the youngest. Jeff turned 49 a couple of weeks back, so in another year, Vit will be the only one of us left who’s under 50. In fact, at the 25th anniversary gig, not just the current band, but three previous Brainstorm Troopers came along: Karl Eastaway (the original singer), Phil Schreck (second drummer) and Mick Lukeis (second bass player). It was a great day. Karl even got up and sang with us on the song Freeway, which is our live anthem. Karl wrote the lyrics and melody at our very first rehearsal, back in June 1988. We arrived at the studio, set up our gear, looked at each other like a bunch of zombies and said, “Hokay! What’ll we play?”

No answer, a bit embarrassing (even for zombies). So we started playing a simple four-chord pattern (Em C D B), very loud, very fast, while Karl sang the first thing that came into his head. We had always wondered what was in there, and it turned out in this case that it was his conversation with Gary our drummer about how to find the rehearsal studio: to wit, “Just follow me and you’ll be right”.

Brilliant. Freeway is a supremely asinine song, which most of the band are very sick of, due to playing it at every gig we did for the first five years of our history. We finally gave it up, but ever since, if we don’t play it, the audience stands there calling for it and refusing to leave till we do it.

AI: Have Brainstorm continued to play live shows throughout the years? In your 1999 interview with Paul you mentioned trying to play at least monthly.

PF: We don’t play live shows much any more, a couple per year, if that. The 25th anniversary gig last year was our first for 2013, and it had been so long since we played in front of an audience that two months of solid rehearsing were needed to bring ourselves up to scratch. That said, it was a lot of fun, one of the most enjoyable shows we’ve ever done.

The rehearsals paid off, because we were tight, loud and in control. When we first went into the rehearsals we decided that we weren’t going to get just up to a standard of passable competence, blunder through some old songs for nostalgia’s sake, have a few drinks with old friends, trying to pretend not to notice all the grey hair and lines on each others’ faces, then go home again. Instead, we decided we’d nail them to the wall, make them remember why they came, why good, loud rock music is so great, and to make them remember that we (Brainstorm) are actually really quite good at this.

We did several songs from Spiral Stair, which no-one had heard yet. Copies of the CD had only arrived the day before the gig, and we were able to sell the first copies of it at the gig. We also played some oldies like Mutants (which also has a good video on Youtube), No Tomorrow, and even the thrash punk song Justice for All off our first album (which I’m guessing you won’t have heard because we’ve never put the first album out on CD).

We also did a couple of brand new covers: Bowie’s Quicksand and (believe it or not) Nights in White Satin by the Moody Blues. And we did them really well, like note for note, but with that immediacy and punch you only get from a live performance.

I’d rehearsed the flute solo in that damned song continuously for weeks and – incredibly – had never played a note wrong. This meant of course that I was terrified that I was certain to completely stuff it up when we finally did it in front of an audience. But I didn’t! Spot on again, every note. Such a relief! It’s a great song, of course, but really well-known songs like that are dangerous to play, because the audience will compare any cover version with the original band’s recording, which they know note for note, and you sound like rubbish even if you falter by the tiniest amount.

Well, we didn’t! No mistakes. They couldn’t believe their ears when we began playing it. It’s not the sort of song people associate with us, especially in amongst loud fast rock songs. They just stared in shock. Surely we weren’t playing Nights in White Satin! Brainstorm don’t play that sort of thing! But the flute solo was exactly right, the vocal harmonies, the rhythm section and (synth) strings, everything worked. By the end they were all singing along, smiling and shaking their heads. We did what we came to do, reminded them that good loud rock music is great to hear played live, and that we were bloody good at it. Nailed ’em! It was a very good gig.

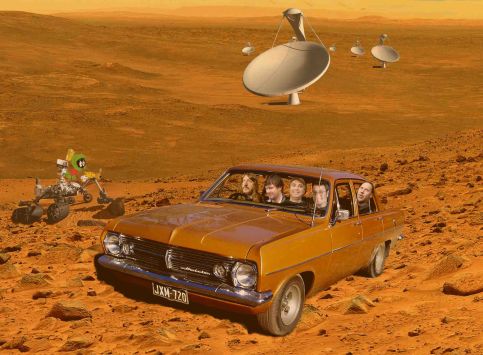

AI: I’ve always loved the picture of the band in the old car soaring through space that appeared on both the first two CDs. I immediately thought of that when I read in your book about how long it would take if a person drove to the moon and back.

PF: The car was Jeff’s, it was named Stonehenge and was indeed beautiful. It was a 1962 S-series Valiant, the Chrysler marque in Australia, which produced cars here for 20 years. My wife also drove one in her younger days, with a 225 cu in slant six engine and push-button auto transmission. The beast is dead now, alas, but lives on in our memories and album art. Long live the beast.

A couple of years ago Jeff came to a band moot with a big grin on his face, saying he’d just realised that one of the latest top of the range Japanese cars had the same power as Stonehenge. Then he stopped and added thoughtfully, as if it had only just occurred to him, “of course, it weighs about 40% less.”

AI: Across the four albums I have, Brainstorm cover a lot of ground musically – Space Rock, 70s styled Progressive and Hard Rock, and even Blues, Folk, Jazz – but though the music is stylistically varied, the lyrics typically have some kind of science/sci-fi/cosmic theme. Are you the chief lyricist?

PF: Yes, although by no means the only one. Actually, I wrote no lyrics on Spiral Stair. I hadn’t realised that before. Interesting. Over the years our style has indeed changed as we learnt more about playing and writing. But any style was fine with us, as long as it was fun to play. Hawkwind was the model for my songwriting, at least, in the early days, because it was easy to do, easy to play, and I had lots of science fiction ideas to use (meaning rip off from years of reading sci fi books) as lyrics. And even Hawkwind music is stylistically very rich. People who don’t love Hawkwind tend to think of just one kind of music, loud, driving, droning, with lots of spacey effects. But Hawkwind music, while distinctly recognisable, is very eclectic in itself.

But we tried many styles. When writing, at the beginning especially, we used to try to emulate a style or song which we liked, trying to achieve the same “feel” as the original. I’m pretty sure that we got away with it because we were so bad at ripping off other people’s material that no-one recognised what we were trying to copy.

But, whether you’re good or bad at it, deliberately choosing a style in which to write a song is a great way to start. By evoking an atmosphere through association with other songs in that milieu, you have a ready-made canvas for counterpoint and departure. One of our conscious and deliberate tricks was – and still is – to work in contrasting sound-scapes, i.e., to write happy music with sad or disturbing lyrics or, alternatively, minor-key music with happy lyrics. It’s an effective way to give a song added impact, both melodically and lyrically.

The other reason for our eclecticism of course is the differing musical backgrounds of the different members of the band, which stem partly from of our different ages. Everyone’s own spiritual home in music is what they listened to as teenagers. Nothing will ever compare with it for personal impact because of the associations a person has as they awaken to the world. Steve and I were 16 in the early seventies, when the best and final evolution of the sixties’ musical journey appeared in the form of progressive rock.

In its broadest sense this includes the best of Hawkwind, Tangerine Dream, Blue Oyster Cult, Pink Floyd, Black Sabbath, Jethro Tull, Mike Oldfield, Focus, Bowie, ELP and a whole slew of others. Of course, we were lucky, because by accident the early seventies also happened to be the time when the best music ever, before or since, was made. It’s not my personal prejudice, or subjective association, but a simple fact, that Close to the Edge is one of perhaps five or six albums from the whole rock era which will still be winning hearts and minds of new listeners in 300 years.

AI: Who are the sci-fi authors who have made the greatest impression on you and why?

PF: Poul Anderson is my great favourite. His books are scientifically clever, complex and exciting, full of those great “how the hell will they get out of this?” plot moments. Bottom line, he’s a born story-teller. A couple of our songs have been based on stories by him, Occupation for one. The other main author in my world, especially as a child growing up in the sixties, was Arthur C Clarke. More broadly, other influences would include Carl Sagan, John Wyndham, Arthur Koestler, Larry Niven, Victor Yeates, Conan Doyle, Orson Scott Card, among many others.

AI: Speaking of variety, there’s no shortage on The Spiral Stair. But I have to single out Das Elektronisches as particularly different and interesting. It starts off cosmic classical, and then transitions to Kraftwerk-gone-Prog Krautrock. How did that tune come about?

PF: Das Elek turned out really well, didn’t it? I’m glad you asked about it, because its story is an unusual one, full of twists and turns. It was basically a jam, or rather two jams, recorded live sitting around in the studio. Both sounded good. We kept trying to develop them into a “proper” track, adding lead parts, harmonies, and so on, but nothing seemed to work them. Whatever we did, just made them sound cluttered. So we put them in the “maybe” bin and worked on other stuff. I can’t remember how long it took, or who it was, who finally realised that the track sounded just fine the way it was, sparse and spacey.

The hardest thing in music is to leave “space” in a track. Silences are so easy to fill, so hard to leave alone. It was by this tortuous process that we came back to where we started, with some very simple and quite good music (Autobahn is another track I still play over and over, regularly).

Steve, Vit and Craig were the main perpetrators of the track. In the end it was their basic ear for good sounds which gave the track its life. Talent is handy for a musician, but not as important as a good ear. You can get away with dodgy skills instrumentally (I’m not talking about Craig, Steve or Vit here, but as a general principle), but when something works you have to be able to spot it, work out what you did, and make sure you don’t lose it in the process of developing it into a song. Several places in Das Elek are like that, serendipitous progressions or relations that came from their skill, or inspired intuition, but which weren’t in themselves deliberate. It took us as a band a long time to realise that we needed to hold back from our normal tendency to overlay more sounds. I suspect that most good music is probably written like that, via experimentation and having the ear to pick out what works and what doesn’t (think of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata).

AI: I recall Paul’s 1999 account of a live Brainstorm performance including three Hawkwind covers in your set. How does Hawkwind fit in as an influence? I got a kick out of your daughter’s description of you in her introductory essay to your book, referring to you as – “looking like a Dalek’s nightmare, Hawkwind blaring out of his mp3 player, earphone wires completely tangled in his glasses and hair.”

PF: You shouldn’t pay too much attention to what my daughter says. A lovely girl in every way, but I have quite a few grey hairs to thank her for and, to be honest and confide in you privately, if she has a fault amidst all that perfection, it’s being sometimes a little too quick to find amusement in the discomfiture and embarrassment of others, especially parents of the father persuasion.

Hawkwind was one of the first bands I got into. In 1972 or 73 a new magazine came out here in Australia called Science Fiction Monthly. I don’t know if it was published overseas in the US or UK. Unlike other sci fi magazines which were just a bit bigger than the size of paperback books and full of words, SFM was a full tabloid sheet, full of brilliant artwork, with just a smattering of words. I remember the awesome Chris Foss covers from Azimov’s Foundation books were amongst them.

Anyway, one of the articles they published was about space rock music, the diffusion of the space theme of the sixties into pop music. They mentioned Pink Floyd, with songs like Interstellar Overdrive and so on, and Tangerine Dream, whose albums Phaedra and Rubycon in particular I still play (on vinyl!) regularly, and then they mentioned this “ultimate” space rock band, named Hawkwind, who wrote songs that were themselves little Science Fiction stories.

A friend of mine went and bought In Search of Space on the strength of the article, and we listened to it for months. I used to record songs off the radio with a microphone into a cassette recorded – often the only way to get them back then – and I still remember the local pop music station in Melbourne announcing, “And here is a new song from young upcoming English band, Hawkwind. It’s called Master of the Universe!”

I bought Space Ritual when it came out. Hawkwind’s main influence was not thematic, however, as I was already into science and science fiction. It was more about freedom, the idea of a whole new way of approaching music, of being able to put anything you liked, anything at all, into a song, to use music as a pure expression of emotions, thoughts and feelings, regardless of commercial success or critical acceptance, just trying to capture in music the essence of the universe, with no critic, no-one to please, other than yourself.

AI: I’m curious about something I saw in the unreleased music section of your web site I saw Theme from Tour of Duty – East Timor (2007), Music written for a documentary called Timor: Tour of Duty by Australian film maker, Sasha Uzunov. What was that? Was the film released with Brainstorm included?

PF: Yes. That music is by Vittorio, our drummer who also plays guitar and keyboards. He’s scary-kind-of-good at everything he does, and loves most of all Jazz. Songs like Unfathomed Darkness and many of the bizarre chord patterns in things like Cyborg are his fault – I mean he wrote them. He already knew the chords, we poor fools brought up on four chords and songs like Ejection and Master of the Universe just had to learn them! The film won a documentary award in the US, and the music is part of the hour or more of tracks that Vit has sitting around, that he’s recorded over the past ten years, which I hope one day that he’ll put out as an album.

Sasha is Vit’s friend and asked him for some music for his documentary. We’d already heard the tracks, I think, and struggled for a while to try to work with them as a band project, but they defeated us, well, me, anyway. Vit’s music is subtler harmonically than anything I’ve worked with before, and only occasionally have we been able to take something of his wholesale and drop it into a song, as a bridge for example, or under a vocal or melodic part. One of the new songs we’re now working on is an example of this, where we’ve been able to meld the band with something Vit has done virtually as a complete piece.

AI: I’m stunned by the numbers of bands who report that more than half their sales anymore are digital. You have an option to buy CDs on your web site, yet you also make all the songs on the albums available for free download. Can you tell me your thoughts about music distribution and selling your CDs vs. letting people download them? The nature of music distribution is evolving so rapidly!

PF: The answer is simple. We haven’t even thought about it! I’m not sure if our (paypal) CD selling system is able to do direct pay-per-track download. It’s something we’ll have to look into, and certainly will, as CD’s are really on the wane as a means of releasing music in general.

At the moment people can listen to any of our songs as mp3’s at okay-but-not-great audio quality, or buy the CD at full hi fi quality. We long ago became reconciled to the strong probability that we’ll never make any money from our music. Some people play golf of the weekend, and spend money on clubs and balls they hit with them into water-traps. Others watch TV, or go down the pub and get pissed. Our free time is spent making music, well, a lot of it, anyway. We equate the cost to any hobby or discretionary activity that we might be interested in. Taking the financial side out of it has been a relief in a way. We’re under no pressure to follow any style or theme other than our own interest, and have no benchmark to aspire to other than our own artistic compass. I can’t see how copyright can continue to exist in an internet world. Pirating is so easy. Everything is available for free, within a day of its release.

Our market is mostly overseas. Australia is a hell of a long way from anywhere. We have 10 out of the 10 deadliest snakes in the world, millions of square miles of desert, and summer heat that hits 46 celsius. Brainstorm are unsigned, independant, financially unviable, and do what we do because we just love music. Style doesn’t matter, just the music. I still cry when someone plays Bette Midler’s The Rose, and get shivers listening to Elvis’ In the Ghetto. At the same time I love melody. At times I think I must have synesthesia, transferrence of perceptions from one sense to another. A good melody to me sounds so good it almost “tastes”. Melodies are the reason for many songs I love. Nightwish’s Nemo is a good example. Just a love song, but, the melody!

The only musical styles I can’t handle are rap and opera, probably for the same reason: they’re modally artificial, musically banal, culturally sterile and lyrically incomprehensible.

These days I get angry at the world more than I used to, so rather than about taking space-ships to the stars, I find myself writing songs about the fact that the Catholic Church is a criminal organisation on par with the Mafia and should be outlawed, or child soldiers in the Congo.

In a way, it’s therapy. I’m a very, very average musician, but when I’m feeling down I can pick up a guitar and start playing. And 20 minutes later I’m back on track again, a little bruised and battered, but back in the land of the living. I feel so sorry for the impotence in people who can’t – or don’t realise how easy it is to – make music. Just pick up a guitar, blow into a flute, chase the blues away.

The web means we can ignore record companies, which won’t sign you up or put out an album unless they’re pretty sure it’s commercially viable. We write music for ourselves. It’s nice to get a few bucks back, but we’re happy ultimately to give our music away. Of course, if someone came along and said, “I’ll give you a million bucks cash up front if you produce an easy-listening MoR album for MTV to massacre”, that would be fine too! But we’d take the money and then get on with our lives. I’d take my share, pack a sleeping bag, telescope, guitar and flute into the 4WD and go bush, to where the road signs say things like, “Warning: Next fuel 670km” and the skies are so clear you can almost touch the stars.

All we want to do is make music, the best we can, to make an honest effort, putting our hearts and souls into it, and then getting it “out there”, to people who might like listening to it. It’s not the only thing we do. But it’s one of the things we do that we’re a bit proud of, and that makes life rich and special. Enjoyment for ourselves and getting our music out to an audience is our only outcome. It’s the only way we measure our “success”. The number of downloads of our songs, as well as the number of hits on our Youtube videos, exceeds our CD sales manyfold. We’re happy, on any basis, just to have people hearing our stuff.

AI: What contemporary bands in the Space/Psych world have excited you in recent years?

PF: Most of the music I listen to is still from the early seventies. My idea of “recent” would be anything since about 1980. Some recent bands which my daughters have got me interested in are Ayreon, Mostly Autumn, Nightwish and Muse.

What really interests me is finding out about bands from the old days that I never knew about at the time. Melbourne is not the centre of the universe. There were whole genres and styles we never heard of back in 1973 that were filling the world with music. I like to go through the band/album review pages on the big prog/space music sites. I read what people have said about them, then go searching on Youtube to find some of their music. A lot of it turns out to be overblown and doesn’t live up to its hype, but from time to time I find music that has just blown me away.

An example is the fourth Gong album. Politically and philosophically I like Gong, but musically they’re often just plain silly. But there are three or four bits on that fourth album, essentially free-form rock/jazz improv stuff, which are superb.

I do it with singles, too. I go through the top 40 charts from the sixties and find songs there that I’d forgotten, then get them from the web and play them. There are lots of examples, but the most recent one was Hank B Marvin’s “Sasha”. I’d completely forgotten about it, till I saw it on an old chart. Great track.

Beyond Earth (Bendigo Community Publishing Inc, 2013)

Beyond Earth (Bendigo Community Publishing Inc, 2013)

AI: I think I might be your ideal target audience. I’m fascinated by, though pretty stupid when it comes to science. What was your goal in writing this column? In the Foreward you say you have tried to “clarify complex subjects, though not to simplify them”.

PF: The problem with science is not that most people are dumb, but rather that they lack the language to understand it; most “popular science” writing in newspapers and mainstream media is a dysfunctional exercise in academic hubris, which deliberately (though usually unconsciously) sets out to confuse rather than edify.

People in general are just persuaded that they’re dumb by the assumption in teachers and the media that if they can’t do the maths and pass the university courses, then they must be too stupid to understand science. This perception is reinforced at all levels, and repeats cyclically through their own inability to understand supposedly simple, public-targeted dumbed-down science programs, which are reinforced by the dysfunctional communicators, round and round.

By “clarify without simplifying” I mean that the book does not skirt around difficult topics. Many “popular science” books insult the intelligence of readers by presuming that there is nothing that they can say that will enable the reader to understand the basic idea of what they’re writing about. So they don’t even try. They gloss over core concepts with meaningless hyperbole, replacing the real significance – and true excitement and wonder – of their subject matter with gee-whizzery and sensationalism. They deliver this jumble of nonsense, and then actually tell the reader/viewer that it’s amazing and awesome.

PF: Instead, what I’ve tried to do is offer an honest description and exposition of the astounding world which science has revealed to us. It is often a challenging read, but the subject matter is awesomely fascinating, and understanding it doesn’t depend on prior knowledge of scientific terms or mathematics. If people stick at it they will get there, without losing mental traction in a morass of empty superlatives. Then, if they find it amazing and awesome, the feeling comes from where it should, inside their own minds, not because they’ve been told to feel that way.

AI: In an email exchange, you mentioned going around to local schools to talk about science and running telescope nights. You said you’ve covered nearly 10,000 kids! I can easily see kids having a ball looking through the telescope. But what kinds of topics do you cover when talking? What kind of feedback do you get from the teachers?

PF: That’s 10,000 people over six or seven years, but all the same, yes, it is a lot. Often, sadly, the teachers themselves are victims of flawed teaching, believing in their own minds that they’re not “scientifically minded”. So the cycle continues.

Comments from teachers are often similar to those from kids, that they never realised half of this stuff, and had no idea it was so straightforward. Some of the most amazing questions have come from school-children. Once I found myself explaining the difference between absorbtion spectra and black body radiation to a class of eight year olds. I’d explained that in stars, like in the flames of a gas stove, the blue light comes from hotter gas than the red or yellow light. No problem so far. Then, half an hour later we were talking about the outer planets of the solar system, and they asked, “If that’s true, then why are Neptune and Uranus blue, if they’re really cold?”

AI: An example of something in the book that jarred my understanding is gravity. I always thought of it, quite simply, as a force that holds me on the ground. If I jump up, there’s no lingering… I come right back down. In Newton’s view I was on the right track. But gravity as a field, as a property of space, related to mass… that’s more complicated, yet somehow graspable… and I find my mind returning to simplicity and thinking of blowing bubbles and how they float and fly for a while before bursting on the ground.

PF: The key to it is to realise that the force you feel from the ground beneath you is transmitted through the soles of your feet. The force you exert on a baby-carriage when you push it along is transmitted through the handle. But the “force” of gravity is different. It pushes, or pulls, on every part of you, the skin on the outside of your body, but also the blood and organs and bones inside. It’s a property of space. If gravity was a force like the others, it would hold you down on the ground by pushing down on the top of your head.

If gravity was a force in the conventional sense, it would have to be able to push on your skin, then pass through it like it wasn’t there, then suddenly notice and push on the layer of flesh or bone underneath it, then do the same to that layer and reach through to notice and push on the layer of cells or whatever below that. And so on. This is insane. Gravity doesn’t go across space, from one place to another, like when your arm reaches out to push the handle of the baby carriage. It fills space from within, affecting every part of it.

Our understanding of it is best imagined as a field, a twisting of the space itself which our bodies occupy, rather than something that happens within it, with space sitting in the background as a frame of reference in which we’re located.

AI: I’ve only had one experience with a high(er) end telescope. I was a student at the University of Wyoming and had a chance to look through their telescope, which was pointed at Saturn. There it was, ring and all. Blew my mind. What’s the most powerful telescope you’ve had the opportunity to look through, and what did you see?

PF: The biggest telescope I’ve seen through was a 20″ monster, but it was at a public night when I was much younger and I didn’t get much out of it. Right now, I’ve got a 16″ scope myself, and access to the local astro club’s one, also a 16″ but with a better mirror and located at a better, darker viewing site. These two telescopes are where I’ve had my best times.

At these sizes, you get so much light that the stars you see start to show their colours. Normally, colour vision only kicks in at high light intensities and anything you see through a smaller telescope is basically in black and white.

The details are also much clearer, too. You see the gas of stellar nurseries swirling around in 3D, lit by the newborn stars embedded in it. Globular clusters are pincushions of light taking up the whole field of view. Seen through a big telescope from a dark site, objects are almost photographic in the detail you see.

AI: The overriding theme throughout the book, and the most consist mind blower, is the NUMBERS. And indeed you address this in the first chapter. A million million degrees, a million million million this and that. Looking at the light from a star and it’s been traveling at 300,000 km per second since before the human race evolved. It’s veeeeery difficult to wrap one’s head around such numbers. Or, as you say, the mind recoils at such unscalable vastness.

PF: The single biggest failure in “popular science” books and documentaries is their unwillingness to explain the numbers involved. The writers realise that these numbers are indeed very hard to wrap your head around. So far, so good. But then they fail, they lose their nerve, and their faith in the quality of their audience and readership, and insult them by just finishing lamely, saying, “er dis is a reeeeely big number, like… you should be impressed …”

And the whole thing collapses. Without quantification, you get nowhere. You have to give people models for reference, over and over, to ground them safely when these big numbers start cropping up.

The distance across the USA is three thousand miles. Continent-spanning trips are generally the largest distances that people can readily relate to. They’ve either flown or driven across all or part of the distance, and have a memory of the hours or days spent, watching the scenery go by, endlessly, hour after hour.

Three thousand miles comes out to about 200 million inches. That’s the USA, coast to coast. To say that the Milky Way galaxy contains 400 billion stars is just a big number. But to say that it’s a thousand round trips, New York to LA and back again, measured in inches, is different.

There’s still a lot of work to do, which you can’t avoid if you want the reward at the end, of coming to a real feeling or sense of such a large number.

That’s what I mean by “clarify but not simplify”. I believe that most people have more brains than scientists and so-called science communicators give them credit for, more than they give themselves credit for. You still have to think hard about these sorts of numbers. The mind still recoils, but now you have a tool for understanding them, a means of relating them to something within your personal experience.

We think in models, in pictures. Our consciousness lives in the visual cortex, the part of the brain which evolved to process images, to turn photons falling on the retinas in the back of our eyes into shapes and colours, and then, more than that, into a three-dimensional mental model of the world that surrounds us. This is why we’re Top Species now on this planet, why the fangs and claws of all the wolves and lions and tigers of prehistory still couldn’t beat a bunch of scrawny monkeys like us. We perceived the world so much better than they could, we could think outside the box, predict their behaviour, build traps, make weapons, imagine them and watch them and understand them, and use their weaknesses to destroy them.

The yardstick of using the distance across the continent in inches to grasp large numbers is just one such tool. But it’s an example of the mental power we have, which sleeps just below the surface of everyone’s mind.

AI: As you point out, the human race as a technological civilization is less than 200 years old, a mere blip in our history. And yet we find ourselves already facing significant population, climate, and pollution threats, as well as the threat of nuclear and other weapons. The big challenge we face is societal changes necessary to ensure our COMMON safety. Could you build on the comment you made, wondering if technological civilizations are short lived? Does this suggest that we might die out or destroy ourselves? Or something else/more?

PF: Clearly we might die out or destroy ourselves. It’s a surprise that we’re still here, in some ways, having lived with the hydrogen bomb for over half a century.

In brief, I’m pessimistic short term but optomistic long term. We’re heading for the “fortress first world” scenario in a big way. Overpopulation, the proliferation of weapons, the cynicism of ruling political and economic classes, is inevitably leading to a world where the rich enjoy a lifestyle similar to our own in the west now, while everybody else starves and dies in their millions – probably billions.

At the moment we have hundreds of millions of refugees or their disingenuous semantic equivalent, “internally displaced people”, living hopeless lives in shanty towns and camps. There are billions in poverty, and perhaps a third, say two billion, people on Earth living in reasonable affluence.

Wars are fought almost entirely over resources. The political ideologies of the early twentieth century have become irrelevant luxuries. The affluent will grow fewer but more powerful, the means by which they remain secure will become necessarily more brutal. The refugee camps surrounding Europe, starving people standing there, staring through the wire at us, past the guards with machine guns, watching us overeat our way to diabetes, wasting our lives watching TV sport and soap operas, just because we happen to have been born on the right side of the wire, rightfully haunts every thinking person. People smuggling, warlords, gangs, failed states, these are all pieces of the same jigsaw.

Sooner or later it will come to open war, a nasty war probably. There are already several thermonuclear warheads “missing” from the outlying regions of the old USSR hegemony. One day someone with nothing left to lose will get into a major city and set one off. I think that will be the trigger.

Bear in mind also climate change. Sea levels will rise about a metre this century, which will be bad enough, but it looks now like they’ll rise three metres next century. Even today, there are already over a billion people living within four metres of sea level.

The post-apocalyptic world of the sci fi novels of the fifties will arrive sometime within 200 years, except for isolated pockets protected and ruled by totalitarian military regimes.

Not a great picture, but I can’t see how we can avoid it, unless we do something spectacular. The safest places will be isolated, small but not too small, islands, perhaps countries like New Zealand, which was the sole surviving technological state in the John Wyndham book the Chrysalids.

The two main wildcards are fusion power and space-travel. If we can get a self-sustaining colony on Mars before Earth society collapses, it could flourish without the home-planet’s support. This is the premise of the Brainstorm album Desert World, of course, which is based on the point that there can be no subsistence agricultural paradigm on Mars. Unlike Earth, a high-tech society is essential there, not for luxuries and weapons, but to maintain air and water and food. If a Martian colony is established and survives, it will need to keep a high level of technical knowledge. On Earth, we could happily bomb ourselves back to the caves and still survive. Not so on Mars.

The other is fusion power. If we’re able to mine Helium-3 on the Moon and use it to stop the fossil-fuel pollution of our ecosphere, we could possibly stabilise the climate before society collapses.

The point where stability returns is clearly defined as the point where the population stops growing. This is where we can look forward to the future with something more in mind than damage control. It will happen, whether by war or by will is not yet clear. At the moment, the betting is on war.

With a stable population and a sustainable ecology, automation of all work will happen very quickly. This is what lies behind the unemployment problems of today. We have a money-based economy, but machines are devaluing manufactured goods to almost nothing. The logical conclusion of the process, which of course economists have no idea about, being constitutionally stupid, is what Arthur C Clarke called the “disinvention of work”. We could have a GDP ten times what it is today, everyone educated, fed, clothed, full health care, cars, robots, machines at our beck and call, for about two hours’ work per adult per week. The technology for all this is already there.

And people will be left to do … what? If a thinking being needs to be told what to do when all their physical needs, even medicine, education, and so on, are met, then they’re not a thinking being at all. Eventually, in such a world, people will start to realise some of the options now open to them.

My personal belief is that the next revolution in science will be the understanding of thought, of mind. Every new broadening of our horizon has given us greater power, caused massive social upheaval, and left something more just below the edge of our sight, beyond the reach of the best tools – physical and mental – that we have.

Science is the culprit, the cause behind the world we have today, all that’s good about it and all that’s bad. It’s given us physical power to wipe ourselves out, and to take the planet with us, or to achieve a level of social and personal wealth undreamed of. But what’s left is this thing called mind.

How can a couple of kilos of carbon and water, arranged in a certain particular way, be you and me? This is the next horizon, and when we gropingly come to terms with it, will come new priorities and purposes that make anything we might plan today as stupid and naive as Julius Caesar being asked to design the airline schedules of north America today.

I personally have no idea where it will lead, but I do believe that this is the next horizon, the real wildcard in our future. To stop war, to understand our own natures, to look at the priorities and possibilities of humanity beyond this terrible reptilian territoriality, competetiveness and aggression, and a politicial system that somehow puts accountants of all people in charge, when the value of any manufactured object is so low as to be irrelevant, and money has no meaning any more… what kind of world would that be?

We see it already in our own souls, in our love for others, in the wonder we feel at the universe. We hear it in music and nature, see it in beauty, both natural and created. We even grope towards it in the sad, venal forms that religion takes today. At their cores, nearly all religions are noble, however factually naive and incorrect they may be, and however corrupted and politically perverted they’ve become. The reality of human power structures turns even the best ideas of the past into machines of oppression, deceit and evil. People who seek power are the last who should be given it.

I seem to have strayed from the question, Jerry. What was it again? [Ed. note: You didn’t stray Paul, thank you for the insightful response]

AI: In your Leaving Home chapter you predict that we will be colonizing beyond Earth within a couple centuries. At first I thought that seemed terribly optimistic. But then I reflected, again, on what we’ve accomplished in less than 200 years and its so astonishing that almost anything seems possible. That said, we do seem to be in a bit of a space program slump, without a whole lot happening. Do you see this changing in the short term? The pessimist in me sees us waiting until we’re forced to react to some real threat or “event”.

PF: Unfortunately I agree. The technological advances in the twentieth century which led to the Moon, the electronics universe we inhabit today without which you and I would never have had even the slightest knowledge of each other’s existence, all of it, came about entirely through the obscenity of two world wars and the cold war which followed. The only reason we haven’t had a third world war is the guaranteed destruction of both sides in a nuclear war.

PF: Unfortunately I agree. The technological advances in the twentieth century which led to the Moon, the electronics universe we inhabit today without which you and I would never have had even the slightest knowledge of each other’s existence, all of it, came about entirely through the obscenity of two world wars and the cold war which followed. The only reason we haven’t had a third world war is the guaranteed destruction of both sides in a nuclear war.

Based on projections in the sixties, we could have colonised Mars in 1986. There were individuals who saw both the Wright brothers and Apollo 11 in their lifetimes. The means are there, right now. All it will take is the will to do it.

Personally, I think it will occur suddenly, when some major prize is identified in space. The current best candidate is helium-3, which could give us ultra-cheap, virtually limitless energy, and which is almost certainly lying around in craters and mixed in with the regolith on the Moon.

The resources are even there. We spend $50,000 now per second on war, on weapons, around the globe. It is the most damning of all obscenities. We’re not short of money, we in this glittering, wealthy world with its multi-trillion dollar budget deficits, what we’re short of is courage and intelligence in the places of power where it matters.

Even the conservative (i.e., expensive) cost estimate of colonising Mars, using outmoded concepts from 20 years ago, was only $400 billion. Sure, that’s a lot. We’d have to divert the world’s weapons budget for about three months to get it. About 13 weeks of not paying all the generals and soldiers, not making rockets and bullets and guns. Wouldn’t that be a shame? Why would we want to do that, when all we’d get for it is a pointless, growing, self-supporting, human colony on Mars.

Why don’t we do it? If you find out, tell me, then we’ll both know.

AI: So let’s say we come up with a concrete plan for colonization beyond Earth. Given the vast distances, are we limited to somewhere within the Milky Way? It’s seems that the two big challenges to anything more are, A) The speed-of-light limitation (you mention ion rockers in your Travelling To The Stars chapter); and B) The number of years a human being can possibly live (cryogenics?).

PF: We can’t travel faster than light, though we can get arbitrarily close to it, which dilates time for the travellers on the spacecraft. So yes, with a good enough propulsion system, you could cross interstellar distances, taking hundreds of years of external time but only maybe few years in your own time.

Some propulsion systems on the drawing board could do this, the best being interstellar ramjets, using magnetic fields to sweep up interstellar hydrogen, then fusing it for energy and shooting it out behind as a rocket blast. Technologically we’re not even close to this, but it breaks no actual laws of physics.

Slowboats using cryogenics are also possible, taking tens of thousands of years to get even to relatively nearby star systems, with the colonists in frozen sleep till they’re nearly there. Propulsion system is achievable, using launching lasers, ion drive rockets, light sails or something like this, but the cryogenic technology is miles ahead of anything we can do yet. Also, trusting your life to a machine that’s going to have to work properly, without failing, thousands of years in the future, to wake you up again, is a serious commitment to make.

Faster than light travel. This would be lovely, but we’re talking about physics beyond anything that we now know, whole scientific revolutions ahead of us. We don’t have the least idea how FTL travel might even be theoretically possible. The only reason to keep this on the table at all is as a limiting case – and because it’s such a cool idea, I for one just can’t let it go as completely impossible. To fly to the stars in a few hours, physics be damned, it has to be possible! If that’s a scientific argument, then you’ve got it!

One other way is possible, sending a slowboat using technologies foreshadowed at least by those we have already, but not with frozen people on board, but frozen embryos. Robots wake them up, they grow into babies, robots educate them and then, when they’re ready, they arrive at their destination. There’s a lot of saving in fuel, air, food and so on with this scenario, and though it’s still vastly beyond our capacities today, it looks to me like the most plausible scenario for true human interstellar colonisation with forseeable technologies.

AI: Continuing the theme of the length of human life and the time it takes to travel significant distances, let’s go to your “relativity” chapters. I read the book twice, but read these chapters multiple times, trying to wrap my head around the concept. I’ll allow myself a gross over-simplification: Is the “time” factor in Einstein’s theory, where my time can be passing slower than your time, in any way related to this travelling to the stars stuff?

PF: Yep, as covered in the previous question. The faster you go, the slower your time goes compared to the time of the universe around you. So you could travel to a star in 100 years earth time, but only take 10 years ship time. When you got there, your great grandchildren would be older than you, back on Earth. This is the premise of the Queen song “39”, incidentally, which is about interstellar colonisation, whose lyrics contain the great phrase: “the land that our grandchildren knew”.

AI: In a chapter about the Voyager probes, you say that after reaching a certain distance their cameras were switched off because there was nothing more for them to see. Really? Nothing? When I look up in the sky it’s hard to imagine emptiness. I realize that much of what I see is very old. But… nothing?

PF: I’m pretty sure that the Voyager cameras were optimised to photograph the planets, moons and rings of the gas giant planets the craft encountered, but weren’t much good for imaging stars against the background of a dark sky. So once past their final planetary encounters, there really wasn’t anything for them to see.

The last photo taken by Voyager was suggested by Carl Sagan, and was the only photo ever obtained of the solar system from outside. It shows all the planets, strewn across billions of kilometres of space. But the images are poor and blurry, showing indeed that the camera wasn’t really meant for that sort of thing. An amazing photo, all the same. The cameras used up power, too, which was getting to be in short supply as the probes’ nuclear power sources grew progressively weaker. I’m not certain, but I think this was the story behind their shut-down.

AI: In the Voyager chapter, by nothing I believe you meant nothing to SEE. In your Almost Infinite chapter you got me thinking about something I probably haven’t considered since my youthful days of stoned rambling conversation. Just as the vast numbers are so difficult to comprehend, so is the idea of nothing as in reaching the END of the universe, and/or whatever there was before the big bang. If the universe is ever expanding… expanding into what? How can there be nothing at all? (Oh crap… this is why people believe in God. Takes the pressure off.)

PF: A lot of this started in my youthful days of stoned rambling conversation. The first thing to realise is that God, as described by the religions of the world, doesn’t exist. He’s neither a big old guy with a beard, nor some kind of mystic force. The question of how the universe got here takes us so far out of our intuitive world that nothing we regard as normal is likely to apply. The three dimensions we seem to live in, the flow of time, the whole yesterday-today-tomorrow thing, the anthropomorphic paradigms and presumptions we’re barely aware of making, life, death, learning, knowing, are all on the table.

I’m amazed by the fact that mind is a property of matter, consciousness, perception, love and all the rest of what makes us different from a lump of rock are themselves properties of matter, no different in the end to mass, charge, spin and so on. What we sense in the purpose of life, somewhere in there, structurally, without assuming a god or any external cause, is the Next Step in our exploration of the universe. To understand the nature of mind will be a revolution as far reaching and revolutionary as was the scientific revolution in the seventeenth century.

AI: In your And Tools Made Man chapter, you talk about how we’re experimenting with direct neural interfacing, and imagine everyone having a direct real-time input at a mental level to everyone else. This got me thinking about PHONES. I know people who have no use for a computer anymore because their phone accomplishes everything they need. The damn things really are remarkable. But I commonly see people appearing to be talking to themselves, when in fact they’ve got a thingy in their ear. I foresee people paying to have implants in their brains so they can do what the phones do without needing the device. I don’t think there’s anything twisted about that thinking. I really see it happening. You think we’ve got a problem with government intrusion and hackers today? Imagine them in your HEAD?!! (Well, you did end the chapter with “The reality will be far stranger” : )

PF: Yes, it will. Many of us are already cyborgs, by any objective definition, with artificial parts, mechanical and chemical, keeping us alive and enhancing our quality of life. There’s no qualititative difference between embedding a memory module in your brain and carrying round an address-book and reminder diary.

When those blue-toothy things that people have stuck in their ears become fully integrated as implants, and when they can be activated and controlled by electrical triggers in the brain, i.e., by thoughts, rather than spoken words, we’ll have an awesome tool (for either good or evil). It’s a long way from the first PC’s, back in the early 80’s, isn’t it?

I still remember the first TV remote control I ever saw. It was at a friend’s place. The volume knob on his TV had shorted out, so as soon as you turned the set on it automatically went straight to max volume and stayed there.

His solution consisted of a broom-handle, a pillow and some gaffer (duct) tape. He taped the pillow to the end of the broom-handle, and screwed the legs off the TV so it sat on the floor. Then he propped the pillow in front of the speaker, and was able to change the volume by pushing the pillow up against the speaker grille with varying degrees of force. There was a certain knack to it, but it worked pretty well for a few months, until someone shoved it too hard and put the broom handle through the speaker.

AI: Any good Further Reading suggestions for the science-challenged-but-intrigued you could recommend? (Also take that as a suggested addition if you do a new printing of the book)

PF: Definitely. Try “The Sleepwalkers”, by Arthur Koestler, and “Wrinkles in Time”, by George Smoot. Both are excellent books about the wonder and excitement of science. I re-read them regularly and find new insights every time I do.

CLICK HERE to read the Brainstorm article and interview with Paul Foley that appeared in Aural Innovations #6, April 1999

Review and interview by Jerry Kranitz

Make Believe It Real is the 12th Spirits Burning album and the third to be credited to Spirits Burning and Bridget Wishart. Of course multiple participants are the spirit of Spirits Burning and Make Believe It Real includes 35 musicians in a variety of configurations. In addition to Bridget and ship commander Don Falcone we have members of the extended Hawkwind family – Dave Anderson, Harvey Bainbridge, Steve Bemand, Richard Chadwick, Alan Davey, Paul Hayles, Simon House, and Dan Thompson. Daevid Allen is present as usual, plus Twink, Keith the Bass (Here and Now), Jay Tausig, John Pack (Spaceseed), and more. This is also the first 2-CD Spirits Burning album. Disc 1 features 11 new compositions and disc 2 consists of remixes and songs that were previously only available on compilations.

Make Believe It Real is the 12th Spirits Burning album and the third to be credited to Spirits Burning and Bridget Wishart. Of course multiple participants are the spirit of Spirits Burning and Make Believe It Real includes 35 musicians in a variety of configurations. In addition to Bridget and ship commander Don Falcone we have members of the extended Hawkwind family – Dave Anderson, Harvey Bainbridge, Steve Bemand, Richard Chadwick, Alan Davey, Paul Hayles, Simon House, and Dan Thompson. Daevid Allen is present as usual, plus Twink, Keith the Bass (Here and Now), Jay Tausig, John Pack (Spaceseed), and more. This is also the first 2-CD Spirits Burning album. Disc 1 features 11 new compositions and disc 2 consists of remixes and songs that were previously only available on compilations.

Red Planet Orchestra is the UK based duo of Vincent Rees and Peter Smith, and States of Space is their fourth album in the past year. The set consists of 5 tracks, two of them busting the 30 minute mark, for a full 95 minutes of music. I recall the early 70s albums with the lengthy epics like Tangerine Dream’s Zeit and Klaus Schulze’s Irrlicht, where the 20 or so minute limitation of an LP side clearly was a hindrance. States of Space demonstrates how the CD and digital worlds do seem to be ideal for allowing this kind of music to take off and explore without interruption.

Red Planet Orchestra is the UK based duo of Vincent Rees and Peter Smith, and States of Space is their fourth album in the past year. The set consists of 5 tracks, two of them busting the 30 minute mark, for a full 95 minutes of music. I recall the early 70s albums with the lengthy epics like Tangerine Dream’s Zeit and Klaus Schulze’s Irrlicht, where the 20 or so minute limitation of an LP side clearly was a hindrance. States of Space demonstrates how the CD and digital worlds do seem to be ideal for allowing this kind of music to take off and explore without interruption. Russian Stoner-Psych trio The Re-Stoned are back with their latest album, Totems. The band are the trio of Ilya Lipkin on guitars, bass, mandola, shaman drum, and jew’s harp, Alexander Romanov on bass, and Vladimir Muchnov on drums.

Russian Stoner-Psych trio The Re-Stoned are back with their latest album, Totems. The band are the trio of Ilya Lipkin on guitars, bass, mandola, shaman drum, and jew’s harp, Alexander Romanov on bass, and Vladimir Muchnov on drums. The Diaphanoids are the Italian duo of Andrea Bellentani and Simon Maccari, who play a craftily constructed and absolutely brain frying blend of Trance, Acid-Psych, 70s Krautrock and Space Rock, and they throw in the kitchen sink for good measure.

The Diaphanoids are the Italian duo of Andrea Bellentani and Simon Maccari, who play a craftily constructed and absolutely brain frying blend of Trance, Acid-Psych, 70s Krautrock and Space Rock, and they throw in the kitchen sink for good measure. Philip Sanderson is a veteran of the UK homemade music/cassette culture underground, his Snatch Tapes label having formed in the heady DIY days of the late 70s. My last run in with Sanderson was his 2012 released Hollow Gravity LP, brought to the world by the Puer Gravy label, run by those creative wild men Eric and Matt of Vas Deferens Organization (VDO).

Philip Sanderson is a veteran of the UK homemade music/cassette culture underground, his Snatch Tapes label having formed in the heady DIY days of the late 70s. My last run in with Sanderson was his 2012 released Hollow Gravity LP, brought to the world by the Puer Gravy label, run by those creative wild men Eric and Matt of Vas Deferens Organization (VDO). Fjodor are a guitar/bass/drums/synths quartet from Croatia, and though new to me, St. Anthony’s Fire is their third album. The album consists of a single 46 minute excursion split across two LP sides. But though it may play as a continuous track, this sucker veers through multiple stylistic twists and turns.

Fjodor are a guitar/bass/drums/synths quartet from Croatia, and though new to me, St. Anthony’s Fire is their third album. The album consists of a single 46 minute excursion split across two LP sides. But though it may play as a continuous track, this sucker veers through multiple stylistic twists and turns. Here we have a split 10″ from Mega Dodo with three songs each from UK based songwriter/musicians Icarus Peel and Mordecai Smyth.

Here we have a split 10″ from Mega Dodo with three songs each from UK based songwriter/musicians Icarus Peel and Mordecai Smyth. Supersound is Italian heavy rockers Void Generator’s first new album I’ve heard since 2010’s Phantom Hell And Soar Angelic, though I see on their web site that they released an EP in 2011. The band are the quartet of Gianmarco Iantaffi on guitar and vocals, Sonia Caporossi on bass (and acoustic guitar on one song), Enrico Cosimi on keyboards and FX, and Marco Cenci on drums.

Supersound is Italian heavy rockers Void Generator’s first new album I’ve heard since 2010’s Phantom Hell And Soar Angelic, though I see on their web site that they released an EP in 2011. The band are the quartet of Gianmarco Iantaffi on guitar and vocals, Sonia Caporossi on bass (and acoustic guitar on one song), Enrico Cosimi on keyboards and FX, and Marco Cenci on drums. Melbourne, Australia based musician Tony Tralongo has been recording since the early 1980s, covering a range of music from Pop to Prog. Spaceship Cocoon is his homage to Krautrock and the Kosmiche music of the 1970s. Tralongo uses virtual synthesizers to emulate the sounds of the era, though there is some guitar on the album and a couple tracks with additional musicians.

Melbourne, Australia based musician Tony Tralongo has been recording since the early 1980s, covering a range of music from Pop to Prog. Spaceship Cocoon is his homage to Krautrock and the Kosmiche music of the 1970s. Tralongo uses virtual synthesizers to emulate the sounds of the era, though there is some guitar on the album and a couple tracks with additional musicians. Brainstorm – “Planetfall” (self-released 2012, CD)

Brainstorm – “Planetfall” (self-released 2012, CD) Brainstorm – “The Spiral Stair” (self-released 2013, CD)

Brainstorm – “The Spiral Stair” (self-released 2013, CD)

Beyond Earth (Bendigo Community Publishing Inc, 2013)

Beyond Earth (Bendigo Community Publishing Inc, 2013) PF: Unfortunately I agree. The technological advances in the twentieth century which led to the Moon, the electronics universe we inhabit today without which you and I would never have had even the slightest knowledge of each other’s existence, all of it, came about entirely through the obscenity of two world wars and the cold war which followed. The only reason we haven’t had a third world war is the guaranteed destruction of both sides in a nuclear war.

PF: Unfortunately I agree. The technological advances in the twentieth century which led to the Moon, the electronics universe we inhabit today without which you and I would never have had even the slightest knowledge of each other’s existence, all of it, came about entirely through the obscenity of two world wars and the cold war which followed. The only reason we haven’t had a third world war is the guaranteed destruction of both sides in a nuclear war.